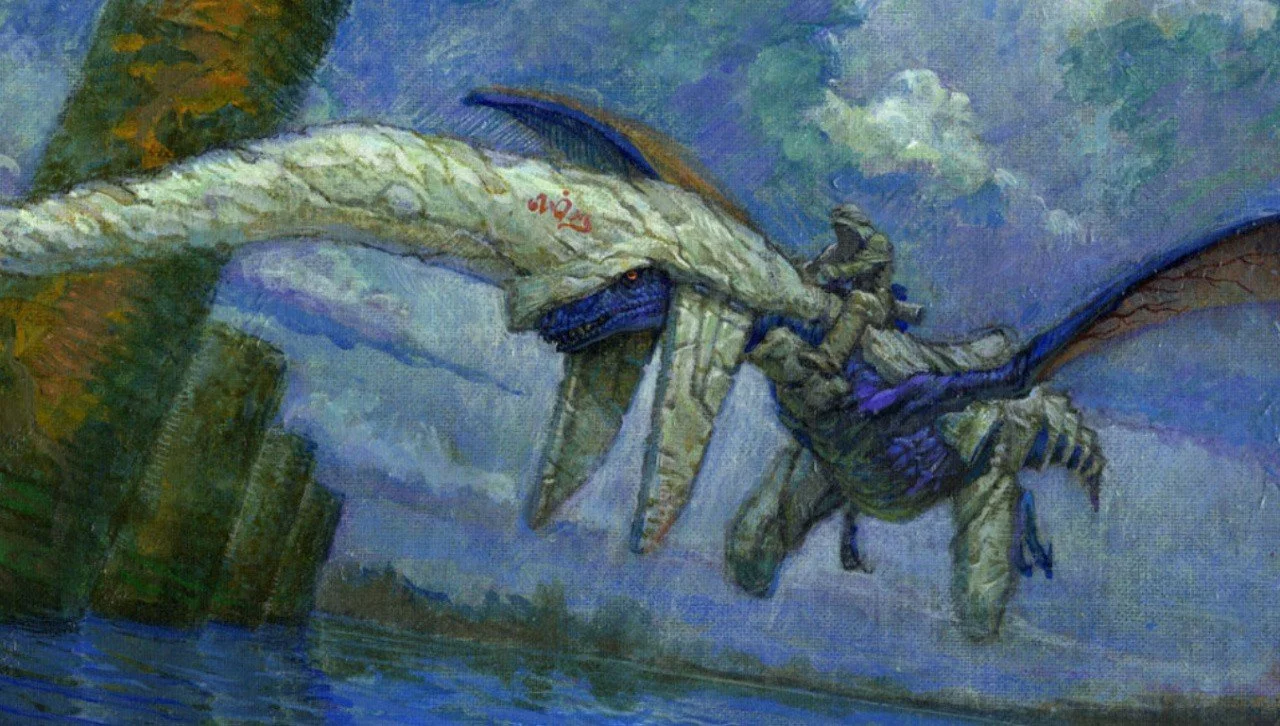

the wings of a blue dragon

On some of the darkest nights of frozen New England winter, my brother and I would sit silently as the balding tires of our family’s Ford F150 slipped along the salted roads. My parents mostly disliked each other, and they sat silent too. We were one of those families that didn’t talk, and my brother and I were children who didn’t ask questions. But we felt a lot.

Later we’d stand in the dry, overheated air of Sears. My mother would walk off, leaving us kids to hover like jellyfish around a father unnecessarily browsing racks of bandsaw blades dappled with rust in their heat-formed plastic coffins. We’d wait for a moment to ask if we could go somewhere, anywhere else.

Eventually it happened. One of us would build the courage to break the silence, and then we were away, kids running amongst the chromium racks of unbought clothing, streaking past the shelves of synthetic leather shoes and underwear and plastic appliances, all destined for the landfill, pointless in the ghost store, itself pointless in a dying mall in a nowhere town.

We ran and the soft slaps of the thin soles of our weathered tennis shoes made thin applause, until we glimpsed the simple paper sign dangling at the end of two thin strings clamped into the drop ceiling: “Electronics.” Like a checkered flag, it spurred us, and here we found our great relief. A small counter tucked into a quiet corner of the store where towers of wire shelves held video games, and amongst these stood a great obelisk, a totem of reverence, a demo kiosk.

It was 1995. The Sega Saturn was just a few months old. A dramatic and expensive thing which my brother and I could only dream of owning, Sega’s most powerful game system sat humming under a plastic bubble shell beneath an elevated television angled perfectly for our young eyes. For the last few months of our weekly visits, it had played a tantalizing loop- the attract demo of Sega’s most ambitious title, Panzer Dragoon.

My brother and I had never seen anything like it. A three-dimensional polygonal dragon soared through endless exotic lands with a rider as small as me perched between its wings. It defied gravity and reality. It carried the weight of the world, and the hopes of all people. Miraculously, if I reached up just a bit to the hovering controller, it could carry me too.

We were spellbound by the dance of wings and light. Every frame of limitless flight atop the shoulders of an armored dragon promised a reimagined life, one in which we could move with agency, destroy or escape that which hurt us. A soaring orchestral score rang through the quiet space. Photons beamed from the CRT and danced against our retinas. Our brains and bodies were literally filled with the light and sound of fantastic places, and hope, and for a few moments once a week, my brother and I did not know the nearness of our unhappiness.

But all things end. The demo would allow us to play for just fifteen minutes, after which the system would die as suddenly as if the power cable had been ripped from the wall. And it happened, as always, in a startling flash of light, after which the screen would go black, and for the briefest of moments we would see ourselves reflected, distorted and small in the convex shadows of the empty screen. We’d see the cavernous emptiness of the ghost store, and the worn linoleum tiles, and the hollow pinholes of the drop ceiling and the racks and racks of pointless shit expensive and expansive, stretching into the shadows. Our smiles would fade and we’d avoid the gaze of our shadowed selves until the Sega Saturn once more fired to electric life.

Then we could once again fly, and we did, until called away. And we’d again go silent and tread lightly. On eggshells. Waiting for it all to cycle again.

I didn’t understand my desperation then. In single digits, you’re too involved in living your small life to really know anything about it. Your reality feels like the only possible reality. Only now, looking back from the vantage point of my fifth decade of life and with two small children of my own, have I begun to understand just how bad our childhoods were.

One year after my first flight atop a winged savior, my family would be broken. My mother gone, my brother missing, my father ordered by a well-meaning court to have no contact with his kids, and me, left to live alone amidst echoes and ghosts, in the stale basement of an elderly unmarried relative who may as well have been a stranger. During these months of isolation, there were spans of days where I’d not hear another human voice. It was then that a deep well was dug in me from which a sadness springs even today. This sadness burbles up from somewhere endlessly and saturates my life. It fills me sometimes, and threatens to capsize me. It demands continuous bailing.

Today, my life is good. It has been highly functional, and there’s a lot for me to love and to be happy about. But I know that I will never be happy the way that some others are happy.

That’s okay.

Tomorrow will be a new weekend. I’ll get up and make my wife a coffee in the morning and deliver it with love. I’ll wake my two daughters with gentle care and make them breakfast. Later, needing groceries maybe, I’ll ask if they’d like to come, and if they do, we’ll go to the big store which happens to have a video game section.

There they’ll find the bright red kiosk and the hovering Nintendo Switch, and their little feet will carry them to it, and they’ll grip the controllers and laugh and play and find happiness as the photons dance against their retinas and the music of adventure vibrates their bones. And when the demo ends, their smiles and laughter will continue, because their childhood will be one of happiness. Their joy will not demand a winged escape or a dragon to carry them. I’ll watch them play, and smile to know that for as long as we’re able, my wife and I will lift them, carry them.

We’ll help them to fly, and that will be enough.